Essay by Salil Tripathi

The people of Bangladesh, who make this golden land their home have come to accept forced displacement as an integral part of their lives. For centuries, floods, cyclones, drought, poverty, and conflict have forced them to move in large numbers, and to give shelter to those who need it. They understand the mighty rivers and their rhythm; they know the rules that nature sets for them: when they can take their boats out, when to cast the net, when they must return.

They understand the frailty and humanity of nature. The nature of inhumanity is a different matter. The pictures in this book tell the story of what happened to the people of Bangladesh in 1971.

Bangladesh was liberated after a violent war in 1971, as it separated from Pakistan. The world was unprepared to deal with the humanitarian crisis that followed those events of 1971. Bangladesh used to be the eastern wing of Pakistan, the nation that emerged out of colonial, undivided India in 1947, at the end of the British rule in the subcontinent. Pakistan was the new state for the subcontinent’s Muslims. It was divided in two halves – West and East Pakistan, with over 1,000 km of Indian territory separating the two. The eastern wing was more populous and poorer, and in the following years, its grievances rose with the western wing, over discrimination in allocation of resources, jobs in the military and civil service. Bengalis also demanded greater use of the Bangla language in administration, governance, and education.

Many in the east were stunned at the lack of concern in the west when in November 1970 Cyclone Bhola struck East Pakistan, and nearly half a million people died or became homeless. Pakistan, which has been ruled for 34 of its 64 years by armed forces, was under military rule at that time. In the democratic elections that followed, the Pakistan People’s Party won 81 of the 138 seats in the west. In the east, Awami League won 160 of the 162 seats. The Awami League championed Bengali aspirations, and expected to form the government at the centre. But discussions and negotiations dragged on till March.

On the night of March 25, the Pakistani Army launched Operation Searchlight, and arrested Awami League leaders and other Bengali nationalists. The troops, drawn from the west, also attacked the Dhaka University campus, killing many students, academics, and people the army considered their opponents. Subsequent accounts by witnesses, survivors, refugees, and victims of beatings, talk of unending horrors, as Bengali nationalists and religious minorities, including Hindus and Christians, suffered. Academics have documented thousands of cases of sexual violence against women – some of the survivors were bold enough to recount their narratives, but many were too embarrassed to talk of their personal humiliation.

On March 29, the representative of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) in India, F.L. Pijnacker, wrote to his headquarters in Geneva, foreseeing a large influx in India. Within a month, a million refugees had arrived in India. By May, the average daily influx was about 100,000 people, and by the end of the year, the government-estimated figure rose to nearly ten million.

The Indian states of West Bengal, Tripura, Assam, Meghalaya, Bihar, and Madhya Pradesh, hosted most of the 10 million refugees – some 6.8 million lived in camps, while another 3.1 million lived with families, friends, or relatives. By mid-May, 330 camps were established to accommodate four million refugees. Of the 825 camps, West Bengal hosted the largest number of camps – 492, with 4.8 million refugees in camps and another 2.4 million with host families, followed by Tripura (276 camps with some 834,000 refugees, and another half million with families).

The UNHCR coordinated efforts from April that year, and the UN Secretary General U Thant decided that the agency would be the focal point for all relief efforts. It involved mobilising funds, procuring and delivering relief supplies, coordinating with the Indian Government, and organising the distribution of supplies. Several UN agencies – the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF), the World Food Programme (WFP), the World Health Organization (WHO), the Food and Agriculture Organization(FAO) among others – worked together with the Indian Government. UN officials wrote of being “depressed by situation and reign of terror which is obvious in faces of people which are stunned and in some cases expressionless…. Saw many bullet wounded men, women and children. Arson, rape and dispersal is the common topic.” Charles Mace, the Deputy High Commissioner at the UNHCR, said: “Words fail me to describe the human plight we have just seen.” The High Commissioner Sadruddin Aga Khan made several trips to the subcontinent, to familiarise himself with the unfolding crisis so as to seek greater resources from the international community.

The refugee influx required delicate political handling – in some districts, refugees outnumbered local residents, and tensions had to be managed. Tripura, which had a population of 1.5 million, hosted 900,000 refugees by May. Such numbers presented a significant logistical challenge for India and the United Nations.

An estimated 10 million men, women and children were forced to become refugees and many more were internally displaced. To date, it constitutes the single-largest and most rapid instance of forced displacement in recent history, surpassing the better-known cases in the Great Lakes of Africa, the Balkans and Afghanistan.

While the events leading up to the 1971 and the conflict itself are slowly beginning to get documented, the dire situation that the refugees and their hosts faced is less known. In the days before 24-hour cable new channels and social media, radio and newspapers were the primary sources of information, and access to some of the locations was not always easy. Journalists and photographers from South Asia and beyond took grave risks to witness and document the conflict and its humanitarian consequences. Many of the photographs and stories that were published in newspapers managed to help shape public policy towards the crisis.

People took grave risks to witness and document the conflict. The experience of the remarkable photographer Naib Uddin Ahmed is instructive. When a Pakistani officer’s camera wasn’t functioning properly and he brought it to Naib Uddin to repair it, Naib Uddin figured out the problem, but pretended that he needed to do more work. He used the camera to surreptitiously record images of burnt villages and dead bodies, and smuggled them across to India through the Mukti Bahini, as the Bangladeshi freedom fighters were known, He never saw the negatives again but the photographs reached international media, which published them prominently, challenging Pakistani claims that the situation was under control, angering the Pakistani military further.

But this volume captures much of the record of that time. Witness the child, with palpable anger on his face, leading a group of non-violent demonstrators following, walking alone, leading a struggle, reminding one of the poem of the great Bangla poet, Rabindranath Tagore, who wrote the national anthem of India and Bangladesh. Walk Alone, the poem celebrates Mohandas Gandhi, the non-violent apostle of India’s independence. Or the billowing smoke out of a van, as if to reveal the clouds of war gathering over the land. Or the pitiless resignation with which a man drags the carcass of another man killed in the paddy. Another group of protestors, carrying the banner saying “Shadhinota”, or independence.The Mukti Bahini’s women’s brigade, marching in white, carrying the still-forbidden flag of the new nation. The sea of humanity that listens, enraptured, Sheikh MujiburRahman, as he declares at the Ramna Race Course: “Ebarer shongram, amader muktir shongram; ebarer shongram, amader shadhinotar shongram.” (This time the struggle is for our freedom, this time the struggle is for our independence.) There is Maulana Bhashani too, addressing a large crowd.

Then there are those grim images, of bodies cast at a round-about, a body, now bloating, rising up from the swamp. And then that trail of refugees, walking in a line, leaving their home, towards an uncertain future. Some carry their worldly possessions in tin trunks, balanced precariously on their heads; some able to leave with even less, in tiny bundles, with the sole pot they were able to take away. The bundles become their umbrellas, as it begins to pour. Many climb atop buses, some in open top trucks, all headed for the border. Men squatting with tiny aluminum plates turned upside down, waiting for their daily ration of rice and watery dal. Couples huddled under the tarpaulin sheet, plastic sheets. A man walks, carrying an unconscious woman.There, you see the saint of the gutters, Mother Teresa of Calcutta, cradling a child. An old grandmother places her hands on the head of a child, protecting him, her sad face reminiscent of the elderly aunt Indir in Satyajit Ray’s film, Pather Panchali (The Song of the Road). And then the face of the child, crying, unable to understand what the world of grownups has done to his little world.

Some foreign witnesses were expelled. Sidney Schanberg, the New York Times reporter, was asked to leave for his graphic accounts of Pakistani violence. Other reporters who ensured that the conflict wouldn’t get forgotten, included Martin Woollacott of the Guardian, Peter Kann of The Wall Street Journal, and Gavin Young of The Observer. Many Bangladeshi photographers like Aftab Ahmed, Rashid Talukder, and Jalaluddin Haider kept a vivid record of what they saw, so that nobody could deny that it ever happened.

Raghu Rai, the famed Indian photographer, who took pictures of many of the children, cannot forget their haunted faces. When his son saw the photograph of the child crying inconsolably, the boy asked his father: “Why is he crying?” Rai reflects: “We will need to answer to the future generations about the pain that we have caused through the war.” Photographers have been deeply affected by the tragedies that have visited Bangladesh over the years. Marilyn Silverstone, the great Magnum photographer, took many images of emaciated children with bullet wounds. She was affected so much she gradually turned towards Buddhism and away from photography, moving to Nepal. Don McCullin, who took the 1971 photograph of the man carrying the unconscious woman was so affected by what he had seen that all he could recount later was that she made it. She survived.

We know of the heroic survival of the civilians because of the dedication of the photographers and writers who witnessed the atrocities, leaving behind this record so that we can at least say “never again,” and at least try to work towards building a future in which such things don’t happen ever again. The record of conflict in the world since 1971 may dismay us, but these images remind us, starkly, why one must not give up hope, and if necessary, walk alone –eklacholo re, as Tagore wrote.

The refugees walked to border towns like Jessore and Rajshahi which became the conduits through which an estimated 10 million refugees made their way to India between April and December 1971. Itself poor, India opened its doors, assisted by the international community including the UNHCR.

Life was hard for the refugees. Monsoon had set in, causing more complications for the operations amidst continuous, heavy rains. With the accumulation of rainwater, the spectre of diseases like malaria and cholera haunted the camps. Children were suffering from malnutrition and were under-nourished, even as India was diverting massive food stocks for the refugees. Cases of dysentery increased. Even as 100,000 refugees arrived in a single day in Nadia in West Bengal, hospitals tried vainly to add more beds. To service that large a population, there were only some 600 doctors and 800 paramedical personnel, according to contemporary accounts.

Cholera spread rapidly, from 9,500 cases in June to 46,000 in September, and there was a shortage of medicines. Vaccines and dehydration fluid were airlifted to the camps. Hospitals had no beds, and many patients lay on metal sheets on concrete floor. Cases of diarrhoea rose, and flies festered on human waste.

As the images show, many people lived in large pipes and in tent cities. They queued for hours for milk or rice. They stood patiently, carrying the sick, old, and infirm among them, hoping for medicines from international aid workers, keen to stay alive and return home. These images recount their agony vividly: the vacant eyes, the pain on their faces; the despair over a lost life, the anonymity in the crowd; the helplessness over the inability in finding out where one’s loved ones are, or if they are even alive; the celebration of new life as a child is born; the desperate attempts to keep the child alive when the baby is sick; the burial of the dead in a foreign land; the compassion of the aid workers, operating round the clock, tirelessly saving lives; the bureaucrats on shaky tables; the swarming flies, the oppressive heat, the grime and the sweat; the complex arithmetic of trying to match resources with needs; the shared ramshackle umbrellas, the huddling beneath trees, shivering in a tropical downpour; the yearning to return to a free country, one’s home.

Every Indian was affected by the war emotionally, and a sense of solidarity emerged quickly. I was a schoolboy in Bombay (as the city was then known) at that time. I remember posters of Sheikh MujiburRahman, Bangladesh’s first Prime Minister who was then in a Pakistani jail, sold at street corners of my city. I remember Indian newspapers carrying grim accounts of the conflict.Joi Bangla became the slogan with which many Indians greeted one another. Mothers sent food for the refugees; each postal transaction in India required an extra stamp to be stuck for refugee relief, which meant that even the most basic form of communication between Indians contributed towards refugee relief. At my school, we staged a play that I directed, and we donated the proceeds to the Bangla Desh(sic) Aid Committee at Flora Fountain in Bombay.

Beyond South Asia, Edward Kennedy, then a young senator from Massachusetts, came to the camps and cradled babies in his arms and vowed support. George Harrison, the former Beatle, raised global consciousness that August, putting together the Concert for Bangladesh at the Madison Square Gardens, with the sitarist Ravi Shankar, poet-singer Bob Dylan, guitarist Eric Clapton and former Beatles drummer Ringo Starr among many other great performers. The Beat poet Allen Ginsberg heard the plaintive cries and wrote the lyrical anthem, September on Jessore Road.

Millions of fathers in rain

Millions of mothers in pain

Millions of brothers in woe

Millions of sisters nowhere to go

One Million aunts are dying for bread

One Million uncles lamenting the dead

Grandfather millions homeless and sad

Grandmother millions silently mad

Millions of daughters walk in the mud

Millions of children wash in the flood

A Million girls vomit & groan

Millions of families hopeless alone

Millions of souls nineteen seventy one

homeless on Jessore road under grey sun

A million are dead, the million who can

Walk toward Calcutta from East Pakistan

Meanwhile, the conflict continued, with the Bangladeshi liberation force, known as Mukti Bahini, fighting valiantly against the Pakistani Army. The Mukti Bahini fought using innovative guerrilla techniques and used its knowledge of the local terrain to fight the better-armed Pakistani forces. Awami politicians who had managed to escape formed a Bangladeshi government-in-exile in India, from where they documented the atrocities, disseminated information, and sought global attention to their plight. India, facing a massive influx of refugees, lobbied international capitals for greater assistance. When Pakistan attacked Indian airfields in December 1971, India retaliated and joined the war. Pakistani Army surrendered in Dhaka on December 16, 1971; Bangladesh became free.

How many lives were lost in that conflict is a matter of controversy – estimates range between tens of thousands to three million. The actual figure may never be known, but grave crimes against humanity were committed, and many of the perpetrators were not held accountable for what they did. In 2011, Bangladesh has initiated trials against alleged war criminals, some 40 years after the conflict.

Within days of the end of the war, refugees began returning to their new country, Bangladesh, on their own. By the end of January 1972, some six million refugees had returned home. A UNHCR report stated: “Visitors to the camp areas marvelled at the unending streams of people on the trek, walking, riding bicycles and rickshaws, standing on truck platforms, with the single purpose – of reaching as soon as possible their native places in East Bengal. In January, a daily average of 210,000 persons crossed the Bangladesh border.”

Each refugee was given food for the journey, medical assistance, and two weeks of basic rations. There were 271 transit camps in Bangladesh, where they received medical aid, food rations, and free transport. On March 25 1972, a year after the military crackdown, India estimated that only 60,000 refugees still remained in India. However, it is likely that a lot more had quietly integrated in neighbouring villages and towns in India and decided not to return.

In retrospect, the 1971 crisis also forced the UN to respond more effectively to humanitarian challenges and forced displacement around the world. Many lessons learnt from 1971 inform the policies and practices of the UN even today.

In August 1973, the governments of Bangladesh, India, and Pakistan signed an agreement that facilitated simultaneous repatriation of three groups of people: Pakistani prisoners-of-war and civil internees in India; Bengalis in Pakistan; and non-Bengalis in Bangladesh who wanted to be repatriated to Pakistan. Airplanes ferried tens of thousands of people across the three countries in late 1973, in a project overseen by the UNHCR. In the end, some 116,000 Bengalis returned to Bangladesh from Pakistan, 104,000 non-Bengalis left for Pakistan from Bangladesh, and 11,000 Pakistanis left for Pakistan from Nepal.

One wound remained open: the status and citizenship of the Urdu-speaking community, commonly referred to as ‘Biharis’ in Bangladesh. In 1947, they left India for Pakistan, and being in the east, they moved to East Pakistan where they constituted a linguistic minority in a largely Bangla-speaking part of the country. As many of them did not support the independence of Bangladesh, and some among them assisted the Pakistani forces, they were targeted as a community. After the war, some were able to repatriate to Pakistan, while those who remained in Bangladesh were for many years treated as non-nationals, otherwise known as ‘Stranded Pakistanis’. For their own security, they were restricted to specific zones, or camps, around Bangladesh where for many years they were provided with humanitarian assistance. The most prominent of these areas is Geneva Camp near Dhaka, which over the years has transformed from camp into a densely-populated urban slum. On May 19, 2008 the Dhaka High court approved citizenship and voting rights for about 150,000 refugees who were minors at the time of Bangladesh’s war of independence in 1971, and those who were born after would also gain the right to vote.

The story of forced displacement and refugees is never ending in South Asia. In the past 40 years, Bangladesh has had to play host to other refugees, too. In the same decade of gaining independence, 250,000 refugees — an ethnic, linguistic and religious minority with a strong nexus to Bangali culture, commonly referred to as the ‘Rohingya’ — from Myanmar sought asylum in Bangladesh. UNHCR set up camps and provided assistance until they returned a few years later. Again in 1991, 250,000 Rohingya refugees sought asylum in Bangladesh. Some 230,000 repatriated from 1991 until 2005, but today some 30,000 official refugees remain in two refugee camps in southeastern Bangladesh near the border with Myanmar. In addition, there are an estimated 200,000 – 500,000 undocumented Muslim residents of northern Rakhine State in Myanmar who today reside in Bangladesh.

*

This year is the 40th year of Bangladesh’s independence. But it also coincides with the 60th anniversary of the 1951 United Nations Convention relating to the Status of Refugees, as well as the 50th anniversary of the 1961 United Nations Convention on the Reduction of Statelessness, that together have provided a strong international legal framework for the protection of refugees and stateless people around the world. Since achieving its own independence 40 years ago, Bangladesh has brought many unique and compelling perspectives to the global experience of migration, forced displacement and protection of refugees and stateless persons. With the support of the government and the people of Bangladesh, the UNHCR and its sister agencies of the UN and a number of national and international NGOs have provided the assistance the refugee needs.

The images in this volume capture, in frozen frames, the hopelessness and despair of the displaced of one tragic upheaval. But it is not an unremitting saga filled with pathos. The birth of a nation is a matter of joy, and this beautiful land celebrates that, with its swaying paddy, windswept skies, the cheerful boatmen singing soulful songs in its rivers, the ecstasy of the Baul singers, the babble of its cities, the reflective calm of the countryside, and the haunting, elemental mangroves. The refugees longed for that sense of normalcy – and you see it in the curious eyes of the child looking at the new world, in the expectation on the faces of crowds standing with quiet dignity for their turn at the rations, in the joy of an impromptu volleyball match.

Published: December 2, 2011

Recent News

-

The Heartbeat of a Nation: Drik Calendar 2026

Published: August 21, 2025

-

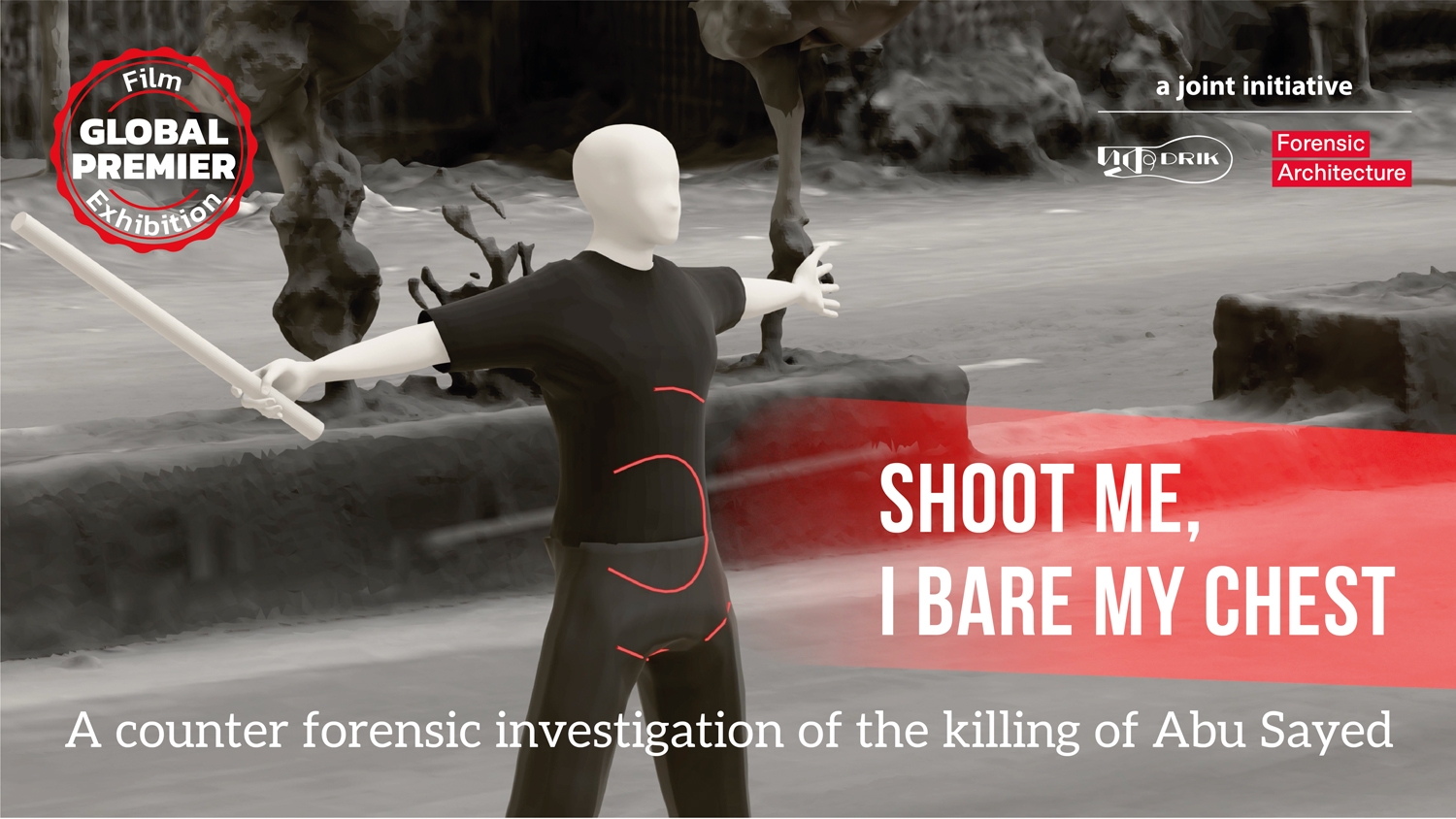

Shoot me, I bare my chest A counter forensic investigation of the killing of Abu Sayed

Published: July 12, 2025

-

Bangladesh Press Photo Contest 2025 Result Announcement

Published: March 25, 2025

-

গণঅভ্যুত্থান পরবর্তী সাংবাদিকতা: সংস্কার ও সম্ভাবনা

Published: January 14, 2025

-

“সোহরাওয়ার্দী উদ্যান যত্নের ডাক” campaign

Published: January 15, 2025

-

Exhibition ‘Border that Bleeds’ by Parvez Ahmad Rony

Published: January 9, 2025