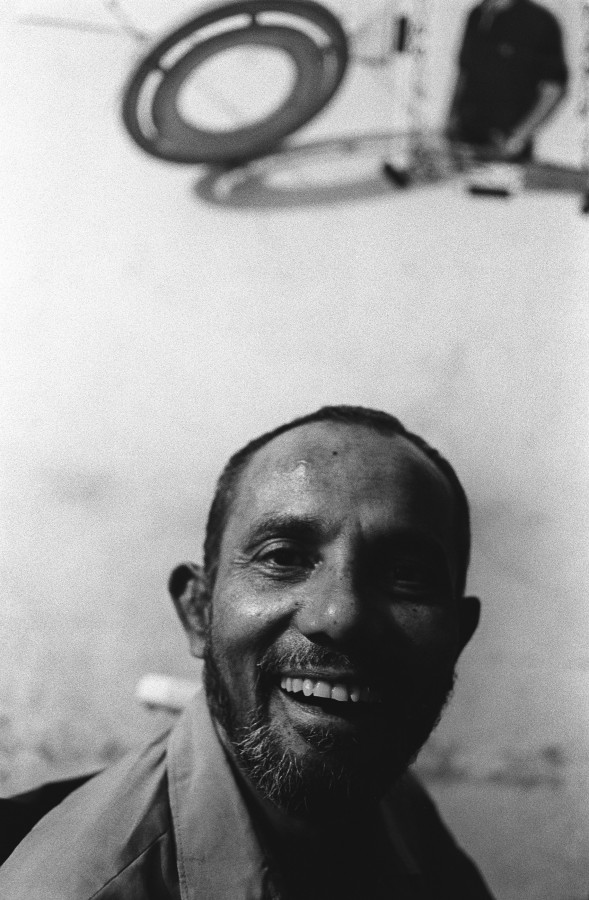

The War Veterans of Bangladesh: Photo story by Abir Abdullah (part of the forthcoming ChobiMela exhibition titled The War We Forgot)

Introduction

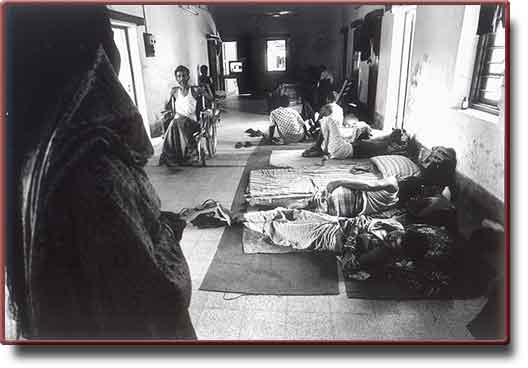

"You remember us for only two or three days a year. Rest of our time is spent on this floor in turmoil and illness" - said Mojai, a veteran of the war of independence of Bangladesh, now a resident of the rehabilitation centre for the war veterans. The life of the wounded and lame war veterans, who took part in the independent war of Bangladesh against the Pakistani Army in 1971, is very much different from the others. The hopes and dreams that led them to go to the war, risk their lives - had all gone in vein. Before the war, lives of mass people in this country had been of dependence and ignorance. Those who fought to change the scenario have now become dependent and highly ignored. The expense of the war has added uncertainties and the trouble of food, cloth and shelter in their lives.

During the post-war era of Bangladesh, the history of liberation took many forms and shapes - as suited by people in power. Thus, it is very difficult to summarise the true history from any textbook or from any formal publication. The newer generation has no notion of what happened during 1971, neither are they interested about it due to ignorance. Most of them don't even know how many people were killed without any reason, or how many women were raped in those nine months. They don't know how many freedom-fighter are still alive - counting their days to death helplessly. Yet, time might come when the mass population might decide to honour the war-veterans properly realising their fault.

Though, however, the true heroes of our liberation might not be able to wait that long. Most of them have their days counted, and many had died already. My photo essay will portray the life and living of the war veterans who are still alive (already three died since I started this work), to make all aware of the degradation we are bringing through neglecting the true heroes of our liberty, as well as documenting whatever truth has remained of our liberation war.

Background

1971. I was very little, and could only stare to the Pakistani Army taking my father away at the middle of the night. The only charge against him was protesting the genocide and rapes by the Pakistani Army over Bangladeshi people. He was taken to the firing squad, and his escape was a miracle. We left our village and came to Dhaka during the war. My elder brother wanted to join the Muktibahini (freedom force), but he wasn’t allowed to do so being the eldest heir of the family. His desire to be a part of the freedom force later found its way through the poems he wrote, mostly on liberation.Time passed and I grew up. Whenever I thought about the post-war Bangladesh and the highly benefited Rajakars (traitors), always an agony filled my heart. When I see the Rajakars holding the top positions of the society, at the same time the poor freedom fighters are deprived from shelter, food and medicine, and overall financial support, it encourages me to keep working on this ground.

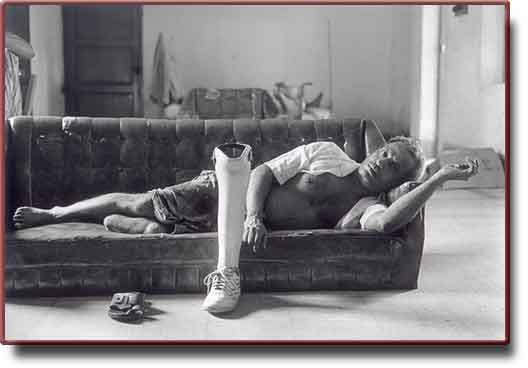

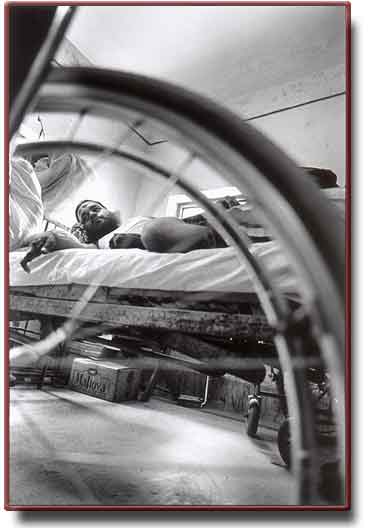

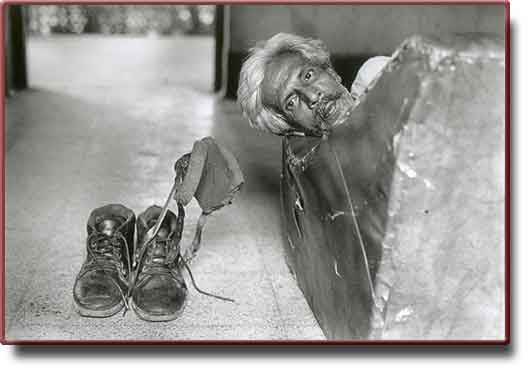

During the nine months of the war, three million people lost their lives. Even thousands more lost their arms and legs. These injured and disabled freedom fighters, who survived all these twenty-eight years of independence, have not yet been properly rehabilitated. Ignored by the nation at large, and hidden away from the mainstream society, their lives stretch ahead — friendless, jobless, and lonely.

I started my work in June, 1997. At first my visits were returned with disbelief and hatred. Different political parties and the journalists — for political and personal gain — had abused the freedom fighters so much! There was no reason as to why they should believe me or help me in any way. And it took some time for me to get real close to them, showing them my work, talking to them, sympathising with their daily lives. Also, the incident of my father and the poems of my elder brother helped a lot. Finally, after nearly six months, I got the pass to get deep into their lives.

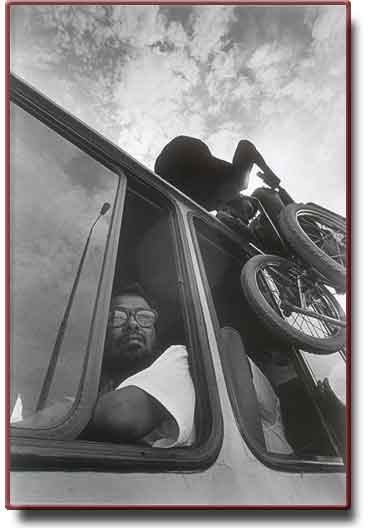

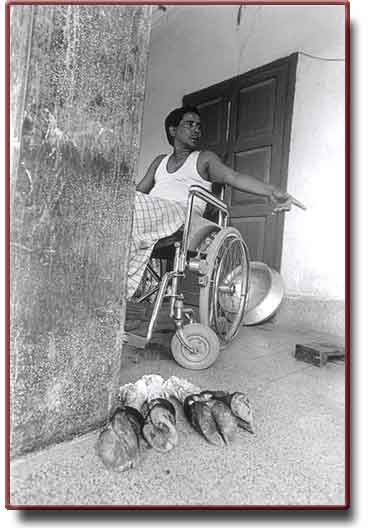

Many freedom fighters pass their time on the floor of the rest house for the wounded freedom fighters, located near College Gate at Mohammadpur in Dhaka, Bangladesh. At times freedom fighters from different villages take shelter in this rest house. Father of the nation, Bangabandhu, came many a time and embraced them while he was alive. Surat Ali, who moves with the aid of a wheel chair, says with resentment, “Merely a hundred yards away, Sheikh Hasina, the daughter of Bangabandhu, lives. And now she is the Prime Minister of Bangladesh, and she doesn’t even come for a day to us.”

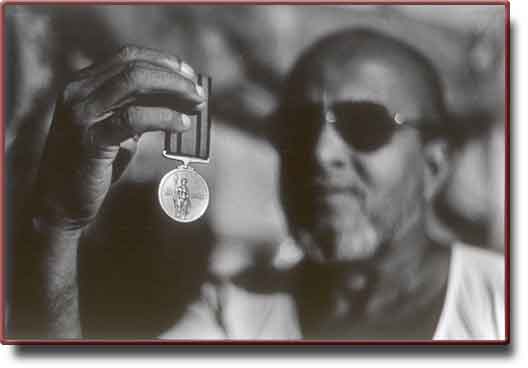

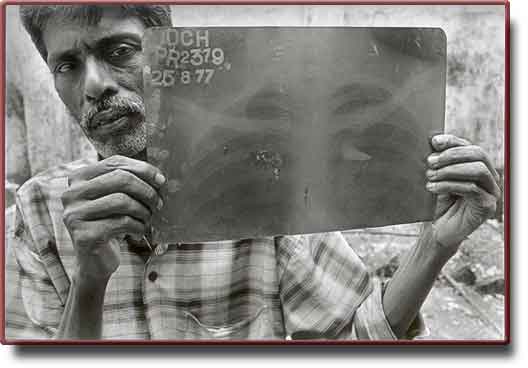

The government has special quota for the freedom fighters at both govt. and public organisations, and persons with forged and false papers usually fill the positions. The true and wounded freedom fighters spend their lives fixed in their wheel chairs, some unable to move without aid from someone else, others unable to acquire a decent job. As they grow older, they suffer from critical diseases that either are very expensive to treat or cannot be cured in this country. As a result, many of them have devoted themselves to god or wear medallions for protection.

Also, only around 1900 freedom fighters get the measure remuneration from the government, and that is only at the major cities. While the number of true wounded freedom fighters is more than a 100 times than this, many of them are still living at the remote places — far away from the facilities of the city — earning their living through pulling rickshaws or begging.

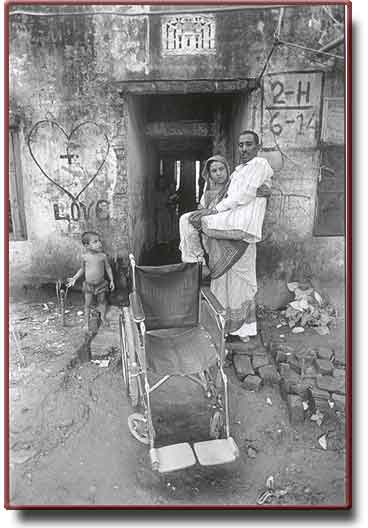

I visited the homes of many injured freedom fighters — homes that were allocated by the government. In many places I found that the homes are not suitable for living. Moreover, the freedom fighters are continuously threatened by the local leaders to abandon the property. Despite several complaints, none of the government officials took any step to protect these helpless freedom fighters.

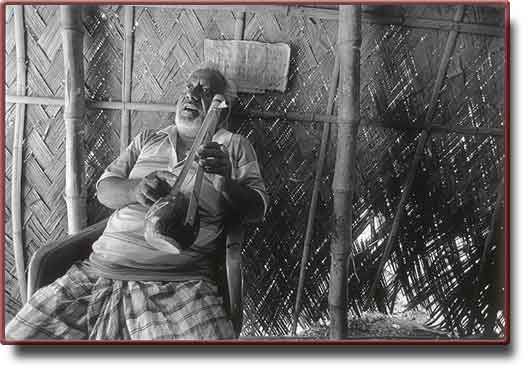

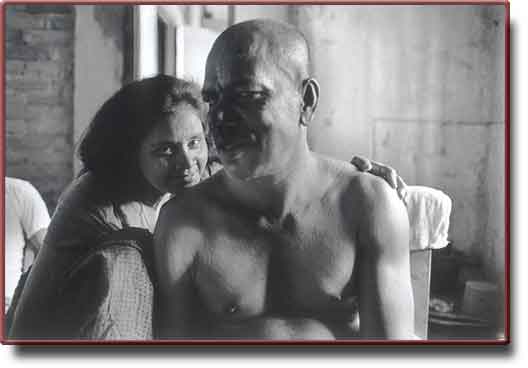

Modhu, one of the wounded freedom fighter, moves from one room to another with the aid of a wheelchair. He doesn’t like to sit idle the whole day. In daytime sometimes he smokes, sometimes plays his guitar, but at night he is sleepless. Modhu’s daughter takes care of her father at times. He enjoys lunch with his daughter. The freedom fighters who stay at the rest house quarrel with each other. Subjects of their arguments are often politics — and their wasted lives. And even sometimes over the card games — just to pass the time.

The wounded freedom fighters didn’t get proper medical aid. They couldn’t get better jobs. Their lives are fixed with their wheel chairs, incapable of motion when no one is there. There is a free medical aid from the government, but they face difficulties in getting the aid. At first they have to inform about their physical problems to the reserve doctor of the ‘Freedom Fighters Welfare Trust’. The doctor then sends a report of the patient to the ‘Trust’. The patient’s condition becomes worse and worse by the time the permission from the ‘Trust’ returns to him.

Out of all the freedom fighters at the ‘Freedom Fighter’s Village’, around 20 to 25 came from outside of Dhaka. In this so-called ‘village’, in every step of their daily life, the freedom fighters have to obey the rules. There are rules for eating, rules for returning home, etc. Their pocket money is Taka 10 per day (approx. 18.5 cents). “We are the guards of this place. We don’t know when or where will be rehabilitated. Above all, we are happy enough that we get two meals here and get a bed with a quilt”, said blind freedom fighter Shafiqur Rahman. He was honoured as a Bir Pratik (Idol of Courage) for his courageous acts in the war. He proudly loves to call himself a Bir Pratik even though his life is spent in misery.

Manik has six sons and four daughters. Liberation is at every step of their daily life — since they are the closest people around Manik. When once I asked Manik if he would send his children to liberation war if there is any coming in future, he strongly answered “definitely”. Though the previous liberation brought him nothing — fame, freedom, at least the acknowledgement — his emotions had been quite strong.

Abul Hossain is another freedom fighter. Two years ago he was watching a drama serial on Television called "the Sword of Tipu Sultan”. At one scene that showed that Tipu Sultan (the patriotic hero) had been defeated. Abul Hossain had a stroke from the reaction and is now paralysed and unable to speak. Abul Hossain still wears a smiling face. His two children stay with their aunt, because the honorarium that he receives from the trust cannot maintain his family of four. Due to the stroke, it seems that he has developed some psychological problems too. Sometimes, without any reason, he smashes everything near him. His wife said with tears “I want my husband to talk and walk like a normal man.” But Abul Hossain’s wife’s desire can never be fulfilled, because on 19 December 1998, Abul Hossain died, snatching away the smile of his own and his family’s.

Throughout the national history the freedom fighters are forgotten at large. I believe, this project will give them a chance to be at least being acknowledged as a part of the history of Bangladesh. This project will also allow the newer generation to know and learn about 1971, the people who fought and suffered during those days to bring them the current happy moments. I believe, this project shall create a scope to mend the bridge between these generations and allow the newer generation to give proper credit and honour to our Freedom Fighters.

Published: February 12, 2000

Recent News

-

The Heartbeat of a Nation: Drik Calendar 2026

Published: August 21, 2025

-

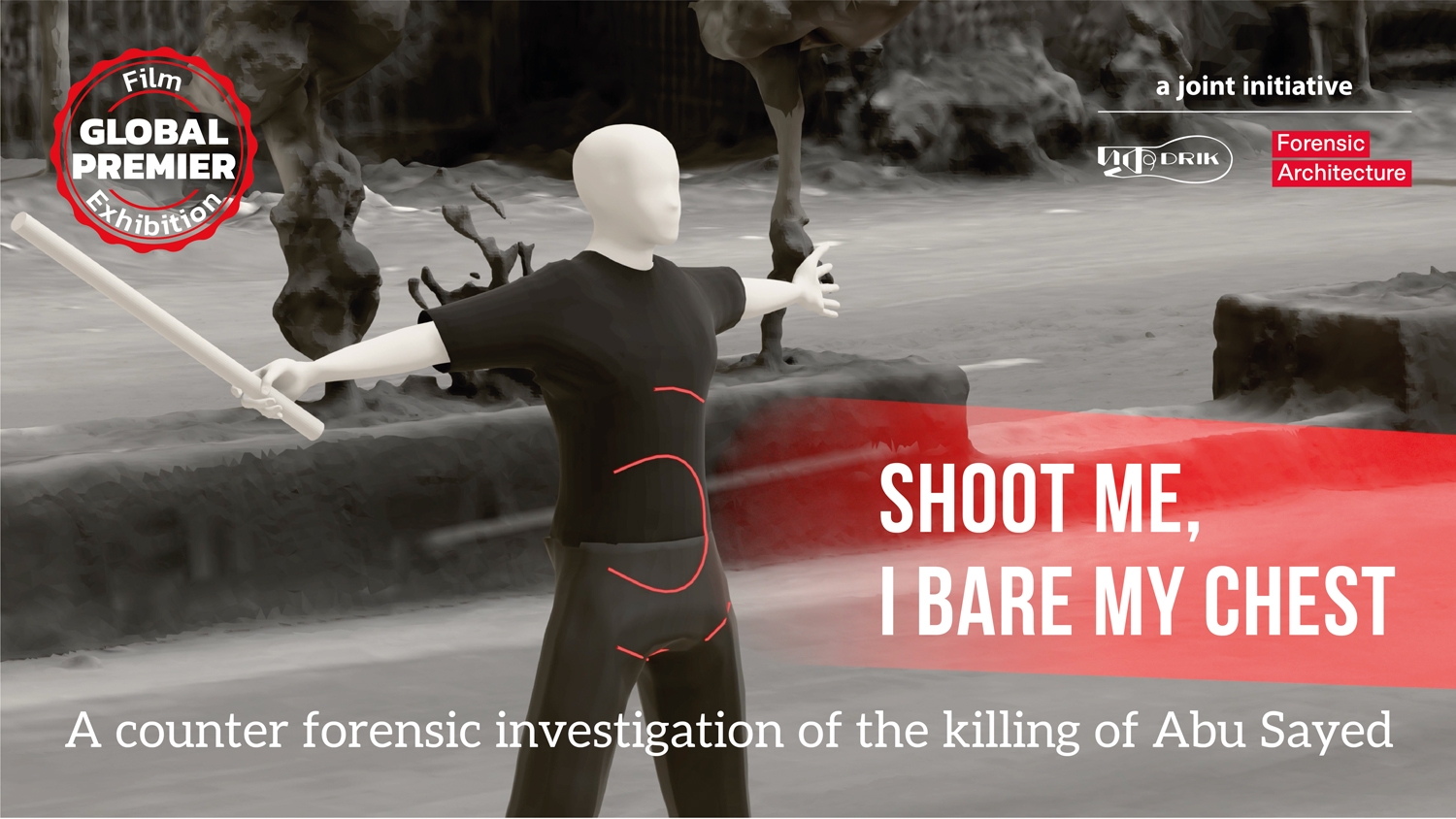

Shoot me, I bare my chest A counter forensic investigation of the killing of Abu Sayed

Published: July 12, 2025

-

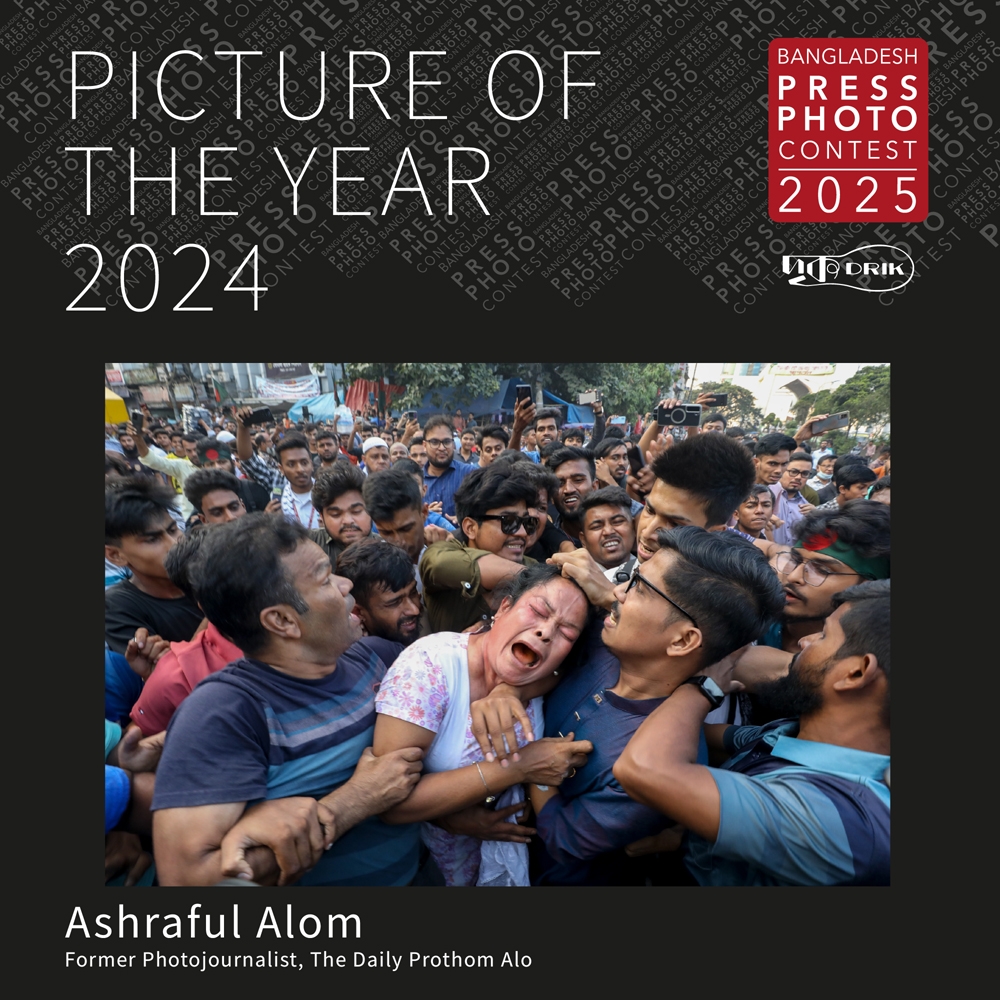

Bangladesh Press Photo Contest 2025 Result Announcement

Published: March 25, 2025

-

গণঅভ্যুত্থান পরবর্তী সাংবাদিকতা: সংস্কার ও সম্ভাবনা

Published: January 14, 2025

-

“সোহরাওয়ার্দী উদ্যান যত্নের ডাক” campaign

Published: January 15, 2025

-

Exhibition ‘Border that Bleeds’ by Parvez Ahmad Rony

Published: January 9, 2025