ART Asia Pacific: Drik images for change, by Antonia Carver

Most art museums in the capitals of the western world would be stunned to achieve attendance figures of over 400,000 for their blockbuster exhibitions. To have this many locals queuing around the block for a photography show at an art-college gallery, with no PR campaign to speak of, is remarkable. In 1990 the photographic agency Drik achieved this for their exhibition 'Struggle for democracy', which was held in Dhaka, Bangladesh, during a time of political unrest when the media had been all but silenced by General Ershad.

![]()

Anti-American demonstrators in Dhaka at the start of the US-led onslaught on Afghanistan, November 2001.

Photograph: G.M.B. Akash/ Drik

Drik began in 1989 in a small house in Dhanmondi, Dhaka. Set up originally as an agency for local photographers, the bedroom was the office, the bathroom a darkroom, and an old metal cabinet the picture library. Mark Sealy, Director of Autograph - the Association of Black Photographers, London - remembers hearing about Drik's ambitious aim to be a 'fully self-funding picture library that would act as a hub for images produced by Bangladeshi and other South Asian photographers'.1

Since then, the agency, whose name comes from the Sanskrit for 'vision', has expanded to include photographers and other media professionals from all over the 'majority world'.2 The library now includes over 100,000 images and the agency is equipped with a state-of-the-art studio and darkroom. New Internationalist magazine describes Drik as 'increasingly important as a hub of creative endeavour and hi-tech communication within the South', a region which, as Michiel Munneke, Managing Director of the World Press Photo Foundation, points out, is generally paid little attention. Drik has also recently launched Pathshala, the South Asian Institute of Photography, and Drik Partnership, a 'global media conglomerate' which currently includes media groups in Norway, Zimbabwe, Tanzania and Uganda.

![]() Drik's gallery opened in 1993 with a World Press Photo Foundation exhibition (now held annually) and has collaborated with photographic agencies such as Magnum and Gamma, as well as local artists. In December 2000 Drik launched 'Chobi Mela', South Asia's first festival of photography, which included eighteen exhibitions, including 'The War We Forgot', a photographic study of the 1971 'War of Liberation' by thirty international photographers, including Don McCullin, Marc Riboud, Mary Ellen Mark, Raghu Rai, Abbas, Rashid Talukder and Kishore Parekh.

Drik's gallery opened in 1993 with a World Press Photo Foundation exhibition (now held annually) and has collaborated with photographic agencies such as Magnum and Gamma, as well as local artists. In December 2000 Drik launched 'Chobi Mela', South Asia's first festival of photography, which included eighteen exhibitions, including 'The War We Forgot', a photographic study of the 1971 'War of Liberation' by thirty international photographers, including Don McCullin, Marc Riboud, Mary Ellen Mark, Raghu Rai, Abbas, Rashid Talukder and Kishore Parekh.

Educational projects range from the local (such as making pinhole cameras with working-class children in Bangladesh) to the global. 'A Tale of Four Cities' involved children from schools and clubs in Dhaka, London, Nairobi and Cape Town sharing their stories and exchanging photographic images and drawings over the Internet. This collaborative project resulted in a fascinating exhibition at The Photographers'Gallery, London, in 1998.

All these activities are supported by Drik's broadband satellite link, which provides an independent revenue stream and has facilitated the launch of Bangladesh's first webzine (Meghbarta) and web portal (Orientation). From a corner of South Asia, Drik has become part of a global network, circumventing the usual lines of controlled communication. (Indeed, Drik's new-media vision is almost a model of what the techie idealists of the 1980s imagined the Internet would be before corporations set up shop.) All in all, the vision is to present a view of the majority world 'not as fodder for disaster reporting, but as a vibrant source of human energy, and a challenge to an exploitative global economic system'.3

![]()

A woman wades through floodwater in Kamlapur, Dhaka, September 1988

Photograph: Shahidul Alam/ Drik

This is very much the drik of Shahidul Alam, the organisation's founder-director. A renowned photographer himself, Alam is currently working on two large-scale, ongoing projects documenting the length and breadth of the Brahmaputra River and the lives of migrant labourers. His belief in the power of images to effect change is fundamental to Drik's activities. In reference to this article he commented that: 'you can have your fancy text, but in a country where the majority are textually illiterate, it is images that communicate'. Or, as Stephen Mayes, Creative Director of eyestorm.com,4 puts it: 'Shahidul is a successful entrepreneur of imagery, except that his profit is not financial. His currency is education and he uses the camera as a tool for social change.' Drik is very much a stakeholder organisation, with key members termed 'family', and international friends and colleagues acting as distant relations.

As Mark Sealy comments: 'Shahidul Alam is one of the most important figures in contemporary photography today, tirelessly working to reclaim the rich visual history of the Bengal Region. He has turned a recognised local need into a major international network.' Eric Peris, a photographer and former editor of Malaysia's New Straits Times, notes that Drik is a 'strong magnet for young photographers, with a keen sense of exploring new areas, always using photography as a medium.'

Drik's growth as an organisation has reflected a key change within photography. As Wendy Watriss has written: 'Classical documentary photography is finding its way not only to remote corners of the world, but into the intimate crevices of the artist's own family and home.'5 Drik photographers tend to do both: they are 'remote' in regard to established networks of photojournalists, agencies and media outlets, and they often turn the camera onto their own worlds. They are the photographed, picking up cameras for themselves, capturing their fellow 'subjects' from the inside out. They also strive, in Alam's words, to be 'interpreters and analysts', rather than 'objective' illustrators of unfolding events.

Abir Abdullah, for example, has made a remarkable, intimate series on the veterans of the Bangladesh Liberation War of 1971. Reading, praying, eating, going about their everyday business, these wounded soldiers have dignity and personality', each image has a story to tell. These are quietly intense photographs, but they tell us as much, maybe more, about the nature of war than any agency snap from the front line. Sameera Huque takes her lens even further behind the scenes, overling reflective portraits of family and friends with snippets of poetic narrative text. Her compositions effortlessly link the present with the struggles of the recent past. Both Abdullah and Huque display a 'typically Drik' approach in their public exploration of personal experience, endowing the twists and turns of the everyday with a powerful political agency.

![]()

![]()

Positive lives, Malaysia.

![]() Photograph: Shahidul Alam/ Drik

Photograph: Shahidul Alam/ Drik

One of Drik's great achievements has been to reach beyond its local situation to cut into international networks. Besides the website and collaborative projects there is a Drik newsgroup where majority-world contributors can post messages, images and personal stories to be read by a wide international audience. This personal, no-holds-barred political approach has made Drik many enemies as well as friends.

In February 2001 all Drik's outgoing phone lines were blocked by the government within 24 hours of the launch of their human rights portal Banglarights.net. Similarly, 'The War We Forgot' exhibition met with a heavy-handed 'request' for certain images to be removed. As Chris Brazier, Co-Editor of New Internationalist magazine, explained:

Here, in Oxford, England, we mount our campaigns for economic justice in relative comfort. The work of Shahidul and his colleagues, in contrast, has frequently been threatened by repression and harassment. The flowering of Drik has taken not just imagination and enormous energy but also no mean degree of courage.

co-editor David Ransom adds:

No doubt Shahidul, and Drik, could live a very much easier life if they abandoned their commitment to the people of Bangladesh and to helping those who wish to express themselves through photographic images. The fact that they have not is, I feel sure, reflected in the strength of the images they produce.

Drik therefore presents a vision of a different kind of arts organisation, one that is highly professional and refuses to be compromised artistically or technically, yet fiercely independent and at work in the most potentially compromising of circumstances. Alam has described Drik as an 'artistic, activist organisation which tries to feed itself.

So what of the future? How will Drik sustain the intimacy of 'family' life as it grows in influence and the extended circle of family and friends gets wider? Alam is well aware of the dangers of growing too fast, of Drik becoming amorphous, of risking the loss of its hard-fought independence. On the other hand, as Michiel Munneke notes, it is important that the organisation 'further professionalises' and ensures that it is self-sustaining in the future. It is a deeply ambitious organisation, aiming on the one hand to be a 'challenge to the CNNs of this world', and on the other hand to be a local force for change. This kind of political stance is often deemed passe by established art organisations and agencies in the West. Drik is establishing a centre for photography and ideas which has no problem with 'audience development' and which remains unbridled in its politics - against all the odds.

_________________________

1 This and all further quotes are from personal correspondence unless otherwise stated.

2 A term coined by Shahidul Alam as an alternative to Third World, used widely by magazines such as the New Internationalist.

3 From an email sent out by Shahidul Alam to subscribers to the Drik yahoo newsgroup.

4 Stephen Mayes was previously chair of the World Press Photo Foundation and director of Network Photographers.

5 . Wendy Watriss, curator essay in BLINK, Phaidon Press, London, 2002, p. 416.

Antonia Carver :

Antonia Carver is a freelance writer and editor. Middle East adviser for ART AsiaPadfic and project editor of BLINK (2002), published by Phaidon Press, London.

Published: May 1, 2002

Recent News

-

The Heartbeat of a Nation: Drik Calendar 2026

Published: August 21, 2025

-

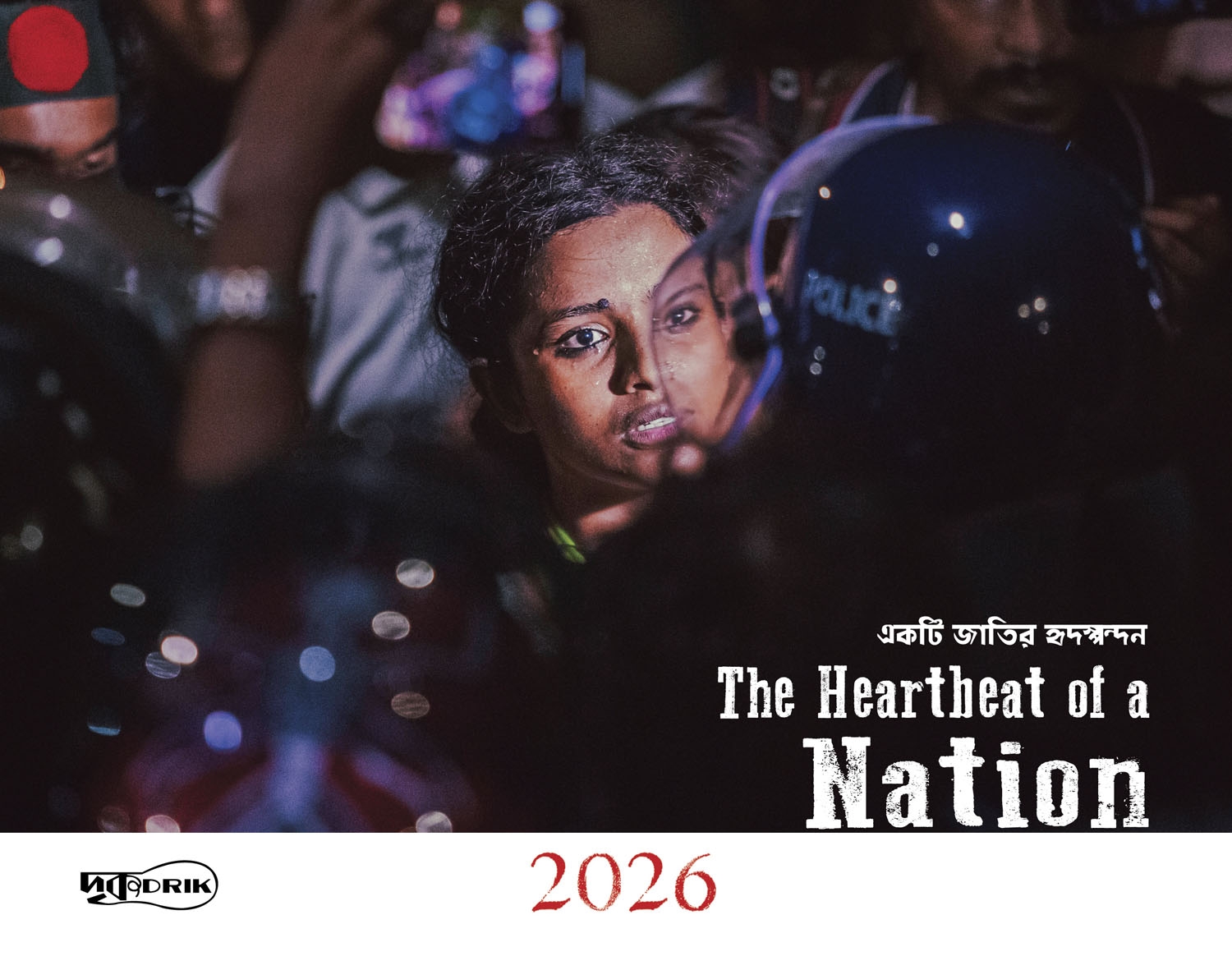

Shoot me, I bare my chest A counter forensic investigation of the killing of Abu Sayed

Published: July 12, 2025

-

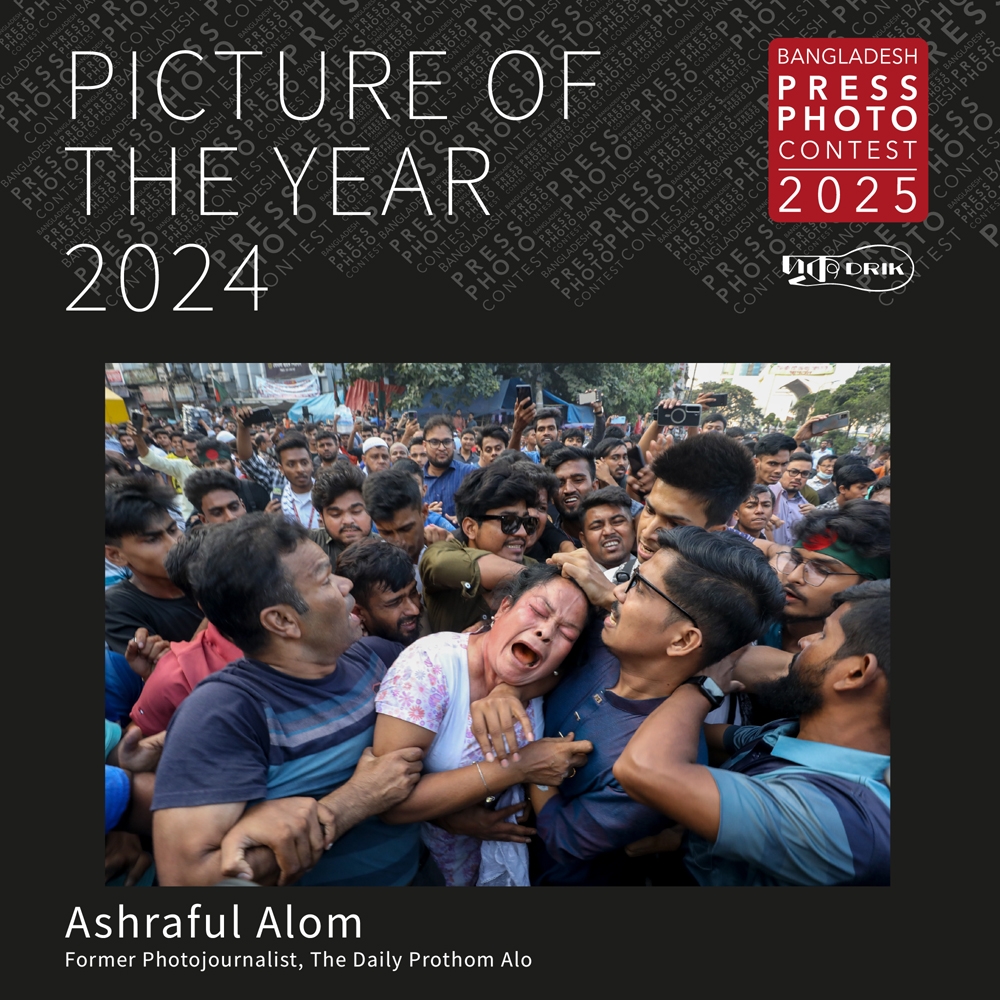

Bangladesh Press Photo Contest 2025 Result Announcement

Published: March 25, 2025

-

গণঅভ্যুত্থান পরবর্তী সাংবাদিকতা: সংস্কার ও সম্ভাবনা

Published: January 14, 2025

-

“সোহরাওয়ার্দী উদ্যান যত্নের ডাক” campaign

Published: January 15, 2025

-

Exhibition ‘Border that Bleeds’ by Parvez Ahmad Rony

Published: January 9, 2025